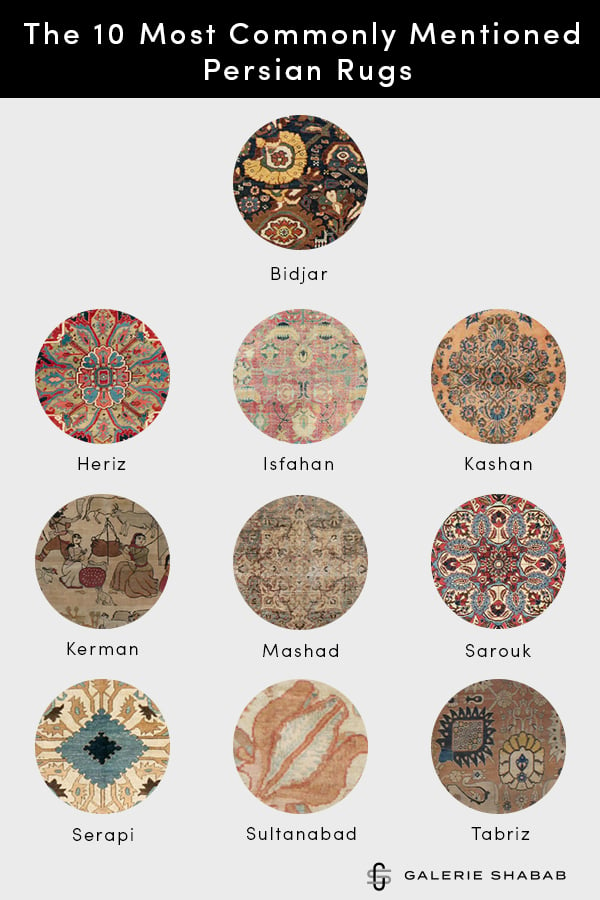

An Introduction to 10 Popular Persian Rug Types

Learn about the Persian rugs you are most likely to hear about when searching for an antique rug.

Persian Bidjar Rugs & Carpets

The Persian branches of the Greater Kurdish Group weave rugs ranging from coarse nomadics to ultra-fine urban creations. Bidjars are the urban “iron carpets,” justly famed for their imposing solidity, compact weaves and wide variety of sizes and formats. Bidjars are presently woven in that city and prior to 1918 in the nearby town of Garrus. There is also a sizable production of scatters woven in the nearby villages, the so-called ‘Kurd Bidjars’. Antique Bidjar rugs are all of all-wool construction, with highly compact piles giving them extraordinary durability. Since about 1920, cotton has partially replaced wool in the foundations, but the board-like texture remains unchanged. Once you have handled a Bidjar, the unique character is never forgotten. Unlike other oriental carpets that derive their long lives from long piles, Bidjars have short, resilient naps, of packed-in, highest quality wool. Density rather than length.

Designs include: large scale ragged palmettes (Harshang), curving ‘fish’ leaves and diamonds (Herati), rosettes and “gooseneck” forked arabesques (Avshan), rosette trellises (Mina Khani), bold split arabesques (“Garrus”), spiral leaves (Mustafi), numerous variations on the medallion and corners, and semi-geometric patterns in the Caucasian / Northwest Persian style.

Dark or navy blue is the most popular basic field tone with warm red, rust, graphite, ivory, goldenrod yellow, light blue and shades of green as supporting tones. The dyes are all natural on antique pieces.

The weaving is carried out in houses and formats include: scatters, design samplers (wagirehs), runners, gallery carpets, long rugs and room sizes rugs to mansion pieces up to 18’ by 28’. Pictorials and prayer rugs are extremely rare.

Although the Kurds have been weaving carpets from time immemorial, extant Bidjars are no older than the early 19th century.

Persian Heriz Rugs & Carpets

Many of the best carpets of the last 150 years have come from the group of villages comprising the Heriz district in northwest Persia. Bold and rustic. Honest and authentic. Direct and unmediated. Most Heriz carpets are in room size format, from 7’ by 9’ to 12’ by 18’, with some giants 27’ in length. There are also scatters and runners. The variations on the medallion and corners pattern are endless, and the vast majority of Heriz carpets are in one or another of these variants, but allover patterns also appear including the Herati (leaves and open diamonds), Harshang (large, ragged palmettes), florals and various lattices. The drawing is always semi-geometric. There are numerous weave grades, ranging from coarse Gorevans to somewhat finer Serapi carpets. Earlier Heriz weavings include the allover pattern Bakshaieshes. Weaving in the area goes back to the 18th century, and the designs, formats and palettes have changed again and again to satisfy the shifting commercial markets, both domestic and export.

While other rug centers have employed synthetic dyes, the Heriz weavers use only naturally dyed wool, with a warm red from madder as the most important tone, and undyed ivory, dark and light blue, salmon, green, camel, yellow, black and rose as secondary shades. There are, however, Heriz carpets with dark blue or ivory grounds, and Gorevans with light blue fields.

The foundations have been all cotton since the later 19th century. The pile, generally of medium height, is sourced from local nomadic sheep.

The borders are often dark blue, with reversing turtle palmettes, or the doubly bent leaf and rosette pattern.

The carpets are created in domestic settings and instead of design sampler mats or paper cartoons, the weavers work from rough sketches or their own imaginations.

Persian Isfahan Rugs & Carpets

Isfahan, located in central Persia is one of the most beautiful and well-preserved cities in the country. The capital from about 1590 to 1800, it has always been a center of art and fine craft with patronage from the rulers on down to a thriving middle class. Carpet weaving ceased in the early 18th century and remained dormant until the early 20th. It was revived and expanded by master weavers dedicated to extremely fine, totally urban creations in the best tradition of the earlier Safavid Court carpets. Isfahan carpets are always designed by specialized artists and are woven from cartoons detailing the color and placement of each knot. The resulting rugs are perfectly balanced, with no hint of weavers coloring outside the lines. They are definitely for the 1% of whatever country they go to.

The foundations are usually silk, and the asymmetric knots are of the finest sheep or goat wool. The knot counts range from 300 to nearly 1000 per square inch and the resilient, closely cut pile shows every design detail. The medallion pattern, with or without matching corners, is the most popular, and details are often carried out in silk of contrasting colors. Palmettes, rosettes, arabesques, rinceaux and leaves are the major design elements, appearing in an ever-changing rendering of designs. Allover and pictorial patterns are also available. Ivory grounds are preferred, often with red borders.

Two generations of the Seirafian family of master weavers have dominated top quality Isfahan weaving and their creations are always signed in a pile cartouche at one end of the rug. All Isfahan rugs are executed in closely supervised factories and there are no household Isfahans worthy of the name.

Persian Kashan Rugs & Carpets

The rather dusty central Persian town of Kashan surprisingly has been a center of the arts for centuries. In Mediaeval times, its pottery and tiles were famous throughout Persia, and later its carpets and velvets were esteemed by rulers and the upper classes. Kashan was an active carpet center in the 16th century and then followed a long period of decline and inactivity, with a revival in the late 19th under the leadership of the Mohtasham family. Although the town is isolated and provincial, the rugs are anything but. Kashan Carpets have all-cotton or occasionally partial silk foundations, short silk or fine wool piles, close to extremely fine knotting and curvilinear designs. The earliest examples show more angularity in pattern, but that learning phase was followed by adherence to knot-by-knot cartoons. The earlier Revival Period carpets employed English Manchester Merino wool, but after the 1920’s, resilient, elastic Persian wool has been the norm. There has always been a small production of silk pile rugs, some with designs raised in relief against flatwoven grounds (souf).

Formats range from mats to large carpets. The classic medallion and corners, often on a rich red ground, is iconic. The tonalities are generally saturated. Dark and medium blue, ivory, green and black are among the most popular secondary tones. Allover patterns include the Shah ‘Abbas designs of various palmettes on a complex vinery. In recent years, the weavers have created abstract, asymmetrical carpets in contemporary taste.

Persian Kerman (Lavar Kerman) Rugs & Carpets

The city of Kerman is located off the beaten track in southeast Persia and its location, unappealing to conquerors, has allowed it to focus on one thing: the weaving of fine and imaginative carpets for more than four centuries. Never being a seat of government, the impetus has always been commercial, and antique Kermans have been found in situ from Turkey to India, and later all across Europe and America.

Always attuned to the latest decorative fashions, the carpets have varied from long format pieces with palmettes and vases in the 17th century to room size pieces with imaginative medallions or unique allover designs involving botehs, palmettes and rinceaux in the 20th. There are numerous single or multiple portrait rugs, as well as pictorials, often hunting carpets or detailing historic sites. Kerman has always placed a strong priority on artistic design and famous designer families go back generations.

The Kerman dyer is also crucial. A Kerman carpet worthy of the names may have twenty or more distinct tones. The red is from cochineal rather than madder, with tones ranging from oxblood to pink to orange. The spectrum of blues and greens is also exceptional. Kermans often use a unique pale pistachio green. While other centers struggle with open ivory grounds, Kerman revels in them. The American market has been the primary recipient for Kermans, and in the 1940’s and 50’s, softly-colored Aubusson-style Kermans were all the rage. The domestic market has always preferred richer, stronger palettes.

The foundations are all-cotton, and the wool is silky, somewhat soft, but resilient. Weaves vary from moderately fine to extremely fine, and there are Kerman scatters with nearly 1000 asymmetric knots per square inch, giving them the character of fine textiles rather than rugs. Carpets are woven in factories with the latest rug loom technology and from scale paper cartoons. There are a very few antique silk-pile Kermans. Many Kermans are dated, signed or inscribed.

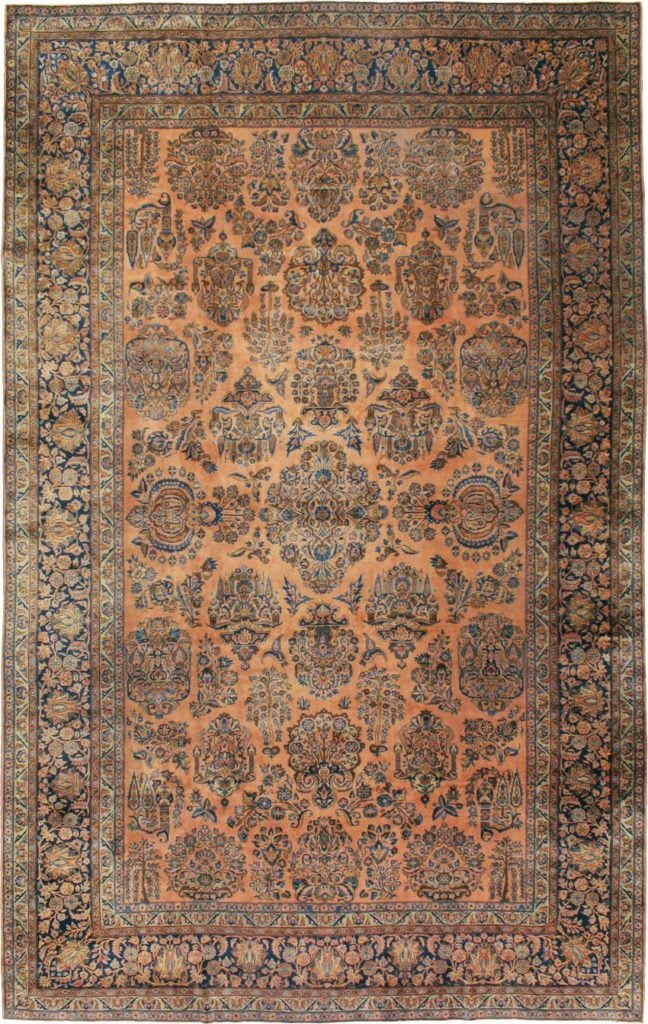

Persian Mashad Rugs & Carpets

Mashad is the largest city in Khorassan Province, northeast Persia and has been an active carpet weaving center since at least the later 16th century. The city is the heart of an extensive carpet weaving district. The many pilgrims coming to the religious shrine leave with a rug or two, sustaining a busy trade. The modern Mashad carpet began, as most Persian rug types did, in the later 19th century. The carpets are woven on all- cotton foundations, some with the traditional asymmetric (Persian) knot, here over four warps (jufti) or the symmetric (Turkish) knot. The piles are clipped relatively short and the wool is particularly soft.

Cochineal, which gives bluer or pinker reds, is favored over madder for the reds, but the rest of the dye palette is standard. The older designs are always curvilinear and feature medallions, palmettes, rosettes, botehs, vinery, forked arabesques and cartouches. The numerous borders provide especially wide frames.

In the twentieth century, certain master weavers, Amoghi (Emogli) the most famous of them, created extremely finely woven, design layered masterpieces for the offices and homes of the new Persian ruling class in Tehran. These rare carpets are a technical and stylistic step above the general Mashad production of the time. In the 1950’s and later some of the leading workshops turned to modern, uncluttered abstract designs in sync with Western interior design trends. These carpets are quite rare.

Mashad carpets appear in all sizes, including giant, oversize pieces up to 20’ by 30’, usually with medallions on open fields.

Mashad carpets are heavy in weight, but the soft wool and jufti knotting may affect the general durability. In most contexts, however, the carpets will perform admirably.

Persian Sarouk Rugs & Carpets

The Sarouk carpet is a relatively recent creation. Before Sarouks, there were Farahan Sarouks and before that Farahans. Numerous villages in the Arak Province of northwest Persia in the 19th century wove Farahans, usually in gallery formats, often with navy allover repeating Herati (leaf and diamond) designs. After WWI, the American market demanded red carpets with navy borders, and the importers were quick to create the “American” style Sarouk with its heavy construction on an all -cotton foundation, moderately close weave of asymmetric (Persian) knots and detached allover floral spray pattern. The texture is leathery and the pile is of medium height, with a smooth, not-quite velvety surface. Thousands and thousands and thousands of them were woven in the villages. From the 1920s through the 1960s it was the most popular large carpet design and probably the most popular oriental carpet type ever. Even today, it is what many people think of as the quintessential Oriental carpet. Sarouks destined for the European or domestic Persian markets often had ivory or blue fields, with classic medallions, or allover palmette and arabesque patterns.

Although most Sarouks are in the 9’ by 12’ size, larger pieces are available. Pieces in top condition exist in numbers. In some cases, vases, botehs, cypresses and bits of architecture enliven the look. A relatively small number of dark blue carpets in the “American” style were woven. In general, the earliest pieces (1920s) are more spacious with more field color visible, and the elements moved closer over time, giving a denser coverage (1940-50).

Persian Serapi Rugs & Carpets

This is a trade name. A grade name given to higher-grade antique Heriz carpets. There is not now and never has been a town called ‘Serapi’ in the Heriz district of northwest Persia in Azerbaijan Province. In fact, the term is downright confusing. The term refers to antique, generally medallion and corners layout carpets of the 1895 to 1915 period of better quality, and can be stretched to fit any well-woven Heriz under consideration, even those of the later interwar period. Some ‘Serapi’s’ have single wefts, some have double, some have flat backs, others are more ridged, but all show symmetric (Turkish) knots on all-cotton foundations. ‘Serapi’ is a grade of Herizes, with Gorevans (there is such a place) at the bottom and ‘Serapis’ at the top. Buy a Heriz, sell a ‘Serapi’.

The dyes are always of good quality, with warm madder reds, indigo blue and undyed ivory, with yellow, rose, green and salmon, all from natural sources. The materials are all handspun. Nothing not authentic here. The weave is somewhat closer than on the usual grades of Herizes, and the pile is clipped shorter. The locally sourced pile wool is more elastic and resilient. The pile stands more erect and this sharpens the motives. The drawing cannot be called curvilinear, but there is an attempt to round the medallions and to make the vinery curve. The Serapi grade is slightly below the contemporaneous Farahan-Sarouks.

The ‘Serapi’ quality is relatively uncommon. The best way to understand the difference is to compare one with a regular quality Heriz.

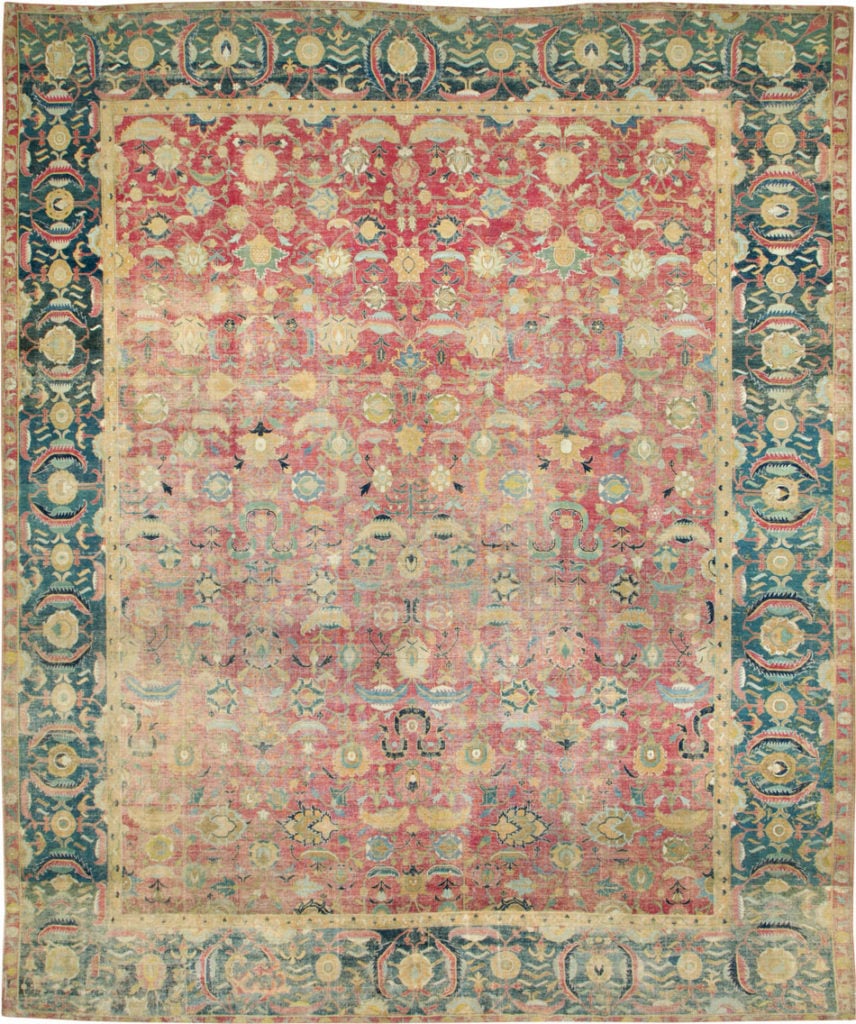

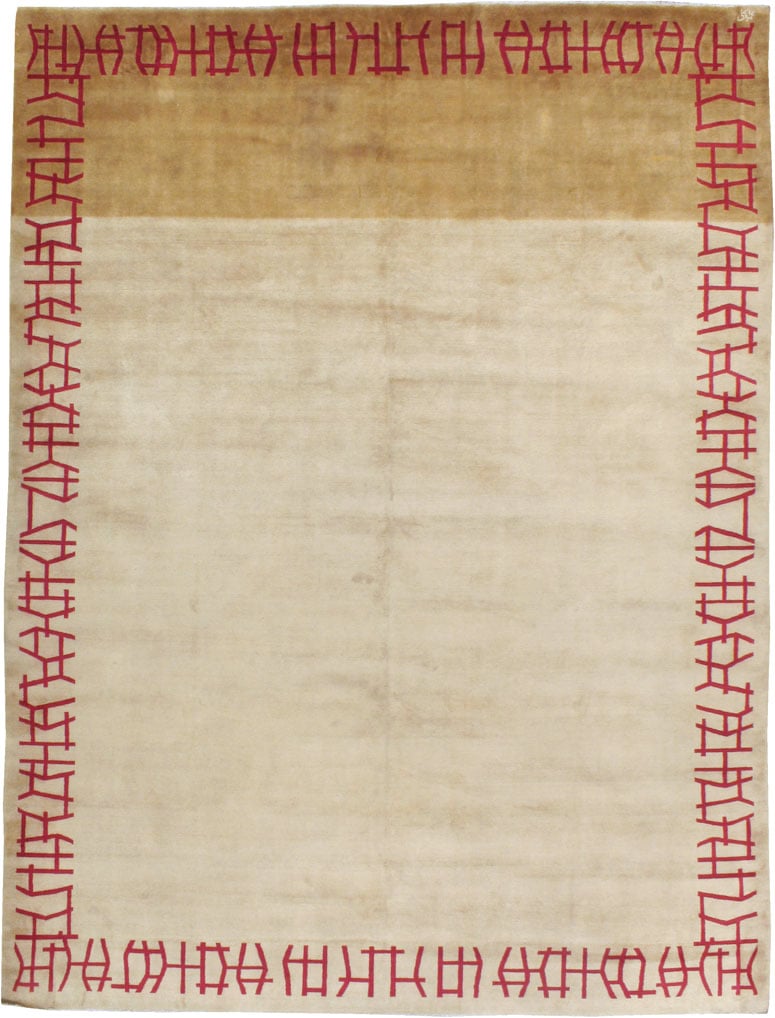

Persian Sultanabad Rugs & Carpets

The Sultanabad district in Persian Arak Province has, over the years, given birth to Sarouk Mahal, Mahal, Mushkabad and Sultanabad carpets. The true Sultanabad, woven between 1885 and 1915 was essentially the creation of the British firm of Ziegler, which dominated the area, producing almost entirely large room size carpets. These highly desirable pieces often have giant floral or palmette allover designs. There are a few medallion or strongly centralized pieces. The palettes are soft, but never subdued. Sizes run somewhat squarish, say 12’ by 14’ to extra-large, 18’ by 24’. All Sultanabads are asymmetrically (Persian) knotted on cotton foundations, in a medium coarse weave. Weaving took place in household workshops, never in factories. The weavers were guided by samplers (wagirehs) and line drawings. They are true rustic pieces. The piles are medium-short and the wool is somewhat soft. They should be kept out of high traffic areas. But they harmonize with almost all decors.

In the Interwar period, the Sultanabad gave way to its close cousin the Mahal. Transitional pieces from the 1920’s could be either, depending on whether one is buying or selling. The price differential is substantial. Authentic Sultanabads in good condition are among the more expensive decorative carpets available today.

Rust reds, light and sky blues, cream, green, straw and pale rose are frequently found as field tones, border colors or as accents. The dyes are generally natural.

They are extremely versatile in pairing with almost any decor, modern or traditional, rustic or highly formal.

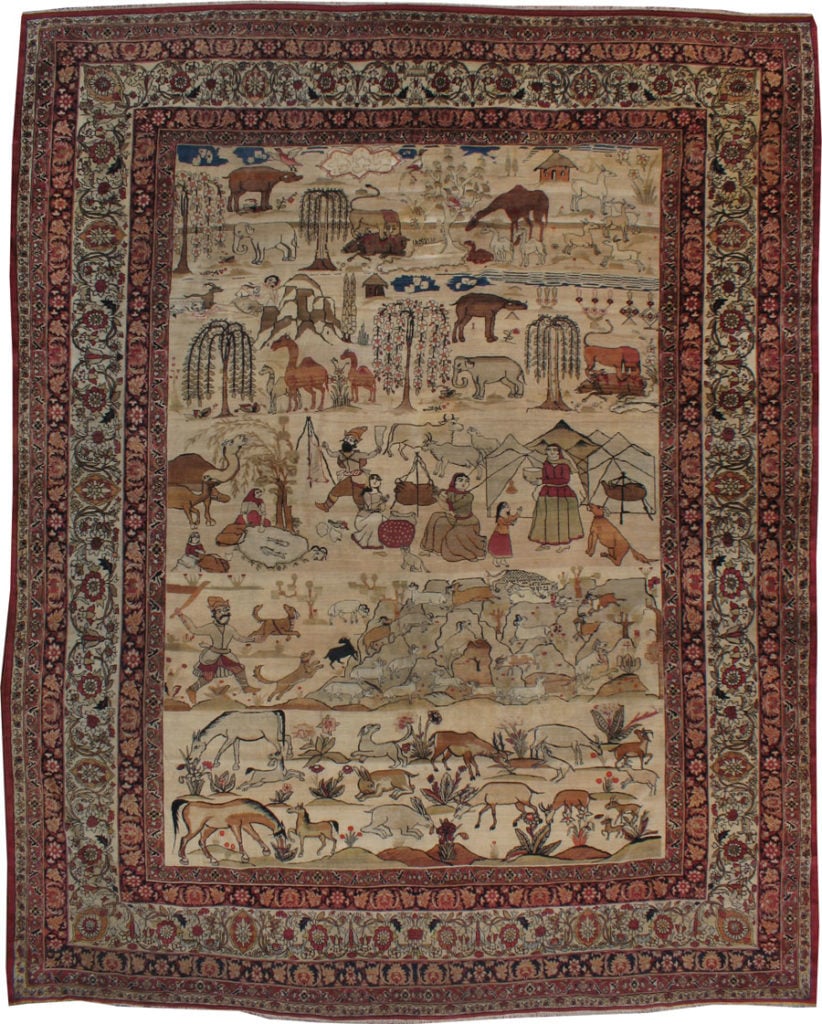

Persian Tabriz Rugs & Carpets

Tabriz in northwest Persia (Azerbaijan Province) was long the nation’s capital, and is still a major commercial and industrial city. The Great Persian Carpet Revival began there in the 1870’s, and ever since it has been a prolific source for urban carpets, rugs and runners in all formats and designs. The designs often reflect classical Persian carpet sources: the panel Garden design; the palmette and vase pattern; the elaborate medallion and matching corners; the Herati (leaves and open diamonds); Harshang (ragged palmettes); as well as scaled up and elaborated Caucasian patterns. Tabriz weavings are often grouped by period. The important “Hajji Jalili” era ran from about 1880 to 1900 and was famed for its open field, beautifully drawn medallion designs, often with copper red open fields. The 1900-1914 period, rugs with animals, demons and a central tree of life were popular export items, their exoticism fitting in with “mysterious East” image. In the Interwar Era, many western exporting firms adopted patterns taken from the illustrated carpet books of the period which depicted classical Persian carpets. Besides wool pile pieces, there has always been a significant production of silk scatters, often in prayer niche layouts, and large silk carpets for the luxury trade. The Tabriz weavers always use the symmetric (Turkish) knot, with short, brushy piles on cotton foundations. Weaves can run anywhere from 65 per square inch to over 400. The finest rugs get the best wool and “Hajji Jalili” pieces have probably the best of all Tabriz wools.

Antique Tabrizes were knotted by boys on upright looms, following detailed cartoons. Today, women do much of the creative labor and the high price of urban real estate has forced many carpet workshops into the surrounding villages. These carpets are still Tabrizes.

Tabrizes are more popular in Europe than in America.

Tabriz carpets are known for their precision and brusque efficiency.

The informal tribal touches, even found on many Persian town carpets, are lacking.